“A willingness to share the delights of the land within the care of the landowner must be safeguarded and the interests of those who make their living from the land protected.”

Forward

The importance of our moorland as a ‘Green Lung’ amidst such a heavily populated urban area is significant and puts our moorland under pressure from people with leisure and mobility as never before. Generally people do not seem to realise that even the most wild and remote places belong to someone. The term “Common Land” is something of a misnomer, common land it is privately owned. Unfortunately, our moorland and the livelihoods of the commoners, the people who have a right of use, is being irreparably damaged by illegal use of vehicles (bikes, 4×4’s, etc.) on the moor. If you see any incident on the moor that you are concerned about it’s important to try and report it by calling the 101 phone number. Doing so ensures the incident is recorded, it generates a log and if a Police off road bike patrol is on duty they might be able to respond.

Rochdale Manor

In the 13th century the Rochdale Manor was held by John de Lacy, the son of Roger who was a renowned soldier and nicknamed “Hell” Lacy for his military daring.

1211 – 1240 John de Lacy was the constable of Chester and a member of one of the oldest, wealthiest and most important baronial families of twelfth and thirteenth century England, with territorial interests distributed widely across the counties of the north Midlands and north. He opposed King John and was one of the barons entrusted with the duty of ensuring that the king kept the agreements made in Magna Carta. By marriage he gained more titles, including that of the Earldom of Lincoln. He also gained the manor and the castle of Bolingbroke. He was buried at Stanlow.

According to the ‘Black Book of Clayton’ (Bodleian Library) John de Lacy held his courts in Rochdale and granted to the knights and free tenants certain privileges for which they had to pay 30 pieces of silver.

1240–1258 Edmund de Lacy,son of John, of whom little is known, except that he was also buried at Stanlow and in 1251 he procured a charter for a weekly market in Rochdale on Wednesday and an annual fair on the feast of St. Simon and St. Jude (28 October).

1258–1311 Henry de Lacy, son of Edmund, was educated at court and became Chief Councillor to Edward I. While the king was engaged on military conflicts with the Scots, Henry was appointed Protector of the Realm. He transferred the monastery from Stanlow to Whalley and died at his London home, Lincoln’s Inn and was buried in the old St Paul’s cathedral.

1311–1322 On the death of Henry the manor descended to an heiress, Alice, who had married Thomas Plantagenet, son of Edmund Crouchback the 1st Earl of Lancaster. Thomas took up arms against Edward II in 1322, however this rebellion was unsuccessful. He was defeated at the Battle of Boroughbridge, imprisoned in his own castle at Pontefract and a few days later he was beheaded outside the city. The manor passed to the crown and for several centuries Rochdale was a Royal Manor.

1610 – An inquisition was held at Rochdale touching the manorial rights and estates, it states that “from time out of mind” a court leet (an ancient English court [A.Sax]; an assembly or convention of the people) had been held at Rochdale twice a year. The inquisition of 1610 provided answers to the King’s Surveyor by a jury of local land owners. We do not know the precise questions but can glean, from the inquiry about Rochdale, some local information for the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

“Spotland conteyneth in yt sixe hamlets – Chadwick, Wolfstenholme, Whitworth, Healey, Falinge.”

“John Holte Esq. holdeth by Knight’s service … and rent payed by himself and tenants in the Manor of Spotland, four score messuages, three water miles, one fulling mill with two stocks, 1,000 acres of land, 300 meadow, 1,000 pasture, 40 wood and underwood in Huddersfield, Spotland and Butterworth. And further he claymeth to hold his Majesty as of his Duchy of Lancaster the third part of the Manor of Rochdale . . .”

“… there be divers and sounder Copiholds lands within the said manor or parish whereof some doe appear to have been holden of Ancient time, others which have lately been some reputed is now injoyed as Copyhold within the space of XXXtie years last past.”

“…the Jury sayeth that there hath been within the space of thirty yeares last past Certayne Wastes Commons or Heathground within the said Parishe of Rachdall some whereof are synce wholly enclosed in some part. The which enclosures or the most of them are now become Copyhold lands and do not yeeld unto his Mjtie the Rent appertaining . . . That is to say one great Waste Comon and heath called Blackeston Edge. . . One other called Knowlemore. . . . One other called Bagsclate . . .”

Local holdings are confined to thirteen surnames, although two others (Bentley & Shepherd) are mentioned:-

| Surname | First Name | Bagslate | Knowl |

| BAMFORD | William | 13¾a 4r | |

| BELFIELD | Christopher | 2½a | |

| CHADWICK | Rodger | 8a 36r | |

| Oliver | 3a | ||

| John | 1¾a 137r | 22a | |

| James | 17½a 1r | ||

| FLETCHER | Laurence | 1a (lately improved) | |

| HARDMAN | John | 14½a 20p | |

| Thomas | (10a 20p (3¾a |

||

| HEWARD | Edmund | ½a 14r | |

| John | ½a 14r | ||

| Roger | 1½a | ||

| HOLT | Francis of Gristlehurst Esq. | 11¼a | |

| John of Stubley Esq. | 7a 34r | ||

| Richard | 3¾a | ||

| Robert | 1a 20r | 2¼a | |

| MARCROFT | Arther | 2a | 36¼a |

| MEADOCROFT | William | 6¾a | |

| RAWSTERNE | Edward | 1¾a | |

| REDFERN | Thomas | 2a 20r | 14½a 20p |

| (also 1a feoffeed by Arthur Bentley and John Shepherd to the use of Thomas Redfern) | 8½a 20p | 6a 20p | |

| Gabriel | 1¾a | ||

| SCHOFIELD | John | 2½a and building and 3 enclosures | |

| Elizeus | 2a 15p | ||

| WOLSTENHOLME | Ffrancis | 69¼a |

Charles I conveyed the manor to the Earl of Holderness who in 1638 sold it for a fee of £2,500 to Sir John Byron (in the 15th century the Byron family were large landowners in Butterworth) who was granted stewardship of the manor and created the Baron of Rochdale for distinguished war services at Edgehill and Worcester. When the parliamentary party became powerful he was declared rebel and his estates confiscated. In 1661 his brother who succeeded to the estates held his court in the town again.

There followed 5 lords Byron including the poet who sold the manor to his steward, James Dearden, in 1832.

Since then the manor has been passed down through the Dearden family. Jeremy James Dearden inherited the Manor in 1980 and was the Lord of the Manor until 2013 when he sold his interest to his brother-in-law, Andrew Scott, who is the current Lord of the Manor.

Definitions

Landowners

Landowners in the area include the Lord of the Manor, the Peel Group and United Utilities.

Steward (Manorial Office)

Estate manager who has the job of supervising or taking care of something, such as an organisation or property.

Moor Looker (Manorial Office)

A voluntary position to “look” over the land in the interest of the manor and the commoners.

Common Land

Common land represents the last remains of the medieval land-tenure system. It is privately owned and known as “Common” because it is generally subject to certain registered rights by one or more persons. Also see the following website: Common Land in England

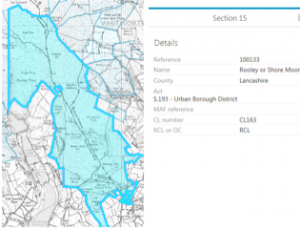

Urban Common

As the name suggests, urban common land is surrounded by urban areas of population. Rooley Moor, for example, is registered as urban common, access rights are under Section 15 (S.193) and not the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000. The effect of section 193 is to preserve the historic access rights on foot or higher rights such as horse riding and their associated management arrangements.

As the name suggests, urban common land is surrounded by urban areas of population. Rooley Moor, for example, is registered as urban common, access rights are under Section 15 (S.193) and not the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000. The effect of section 193 is to preserve the historic access rights on foot or higher rights such as horse riding and their associated management arrangements.

Rights of Common

Rights of common are attached to dwellings and detailed in the deeds and such rights are separately defined in each case. Ancient rights of common were usually of five kinds, although there were others:

- of pasture: the right to graze livestock; the animals permitted, whether sheep, horses, cattle, etc, were specified in each case.

- of estovers: the right to cut and take wood (but not timber), reeds, heather, bracken, etc.

- of turbary: the right to dig turf or peat for fuel.

- in the soil: the right to take sand, gravel, stone, coal, minerals, etc.

- of piscary: the right to take fish from ponds, streams, etc.

These rights related to natural produce, not to crops or commercial exploitation of the land. They were almost always subject to limitations as to quantities (usually enough for the domestic needs of the commoner) and sometimes as to season (e.g. not during game-breeding periods). In modern times, rights have been defined in terms of intangibles such as access to light, air, recreation, etc.

Commoner

Those who have a “Right of Use.”

Laws

All the moorland which is outside the highest wall is registered ‘Common Land’. The landowners and those who have “Right of Use” must always be repaid with respect and responsible behaviour.

You can not enclose the moor, enclosure is against the law. You must only fence against the moor. You can plant a tree, but not three together. You need the consent of commoners to disturb the soil.

Common Land Registration

The war years witnessed much requisitioning of Common Land and the confusion which ensued combined wit the disorder that already existed in some areas, resulted in the setting up of a Royal Commission in 1958. This commission recommended 2 stages of legislation.

Stage 1

Record land which actually was common and to provide for the “Registration of Rights”. This took place in the 1960’s

Stage 2

Provide for a management structure.

Before this

NO farm was viable without its moor right’s. Farming practice dictated the necessity of this because farms were too small to maintain animal husbandry without a right of common grazing. The average amount of “In Bye” (that part of the farm which is used mainly for arable and grassland production and bounded by a fence, a dyke or a hedge and is not hill and rough grazings) land being 6 acres this is too small to be grazed and grow winter fodder too. It was therefore essential that during the gentler months stock could be turned to the moor.

Now

First subsidies and Single Farm Payments

HEL schemes

Changes in farming practice make common grazing essential

Common Land Registers

The common land registers hold details of extents, rights and ownership of common land, as registered under the Commons Registration Act of 1965 and the Commons Act 2006.

Unit numbers

Each area listed in the registers has a unique ‘unit number’, for example:

- CL94, CL99, CL162, CL163, CL163, CL174, CL175 – the prefix CL defines the land as common land

- VG prefix’s define the land as town or village green

Each unit number in the registers is divided into three sections:

Land section

The ‘land section’ includes a description of the land, who applied to register the land, and when the land became finally registered. There are also related plans which show the boundaries of the land.

Rights section

The ‘rights section’ includes a description of the rights of common (for example a right to graze a certain amount of sheep), the area of common over which the right is exercisable, the name of the holder of the right and whether the right is attached to land in the ownership of the holder of the right (the commoner) or is a right held in gross i.e. unattached to land.

Ownership section

The ‘ownership section’ includes details of the owner(s) of the common land. Entries in this section however, are not held to be conclusive.